Built on Slavery: Debt Bondage and Child Labour in Cambodia’s Brick Factories

Published on 2 December 2016On the International Day for the Abolition of Slavery, LICADHO publishes its report "Built on Slavery: Debt Bondage and Child Labour in Cambodia’s Brick Factories” which presents evidence of the widespread use of contemporary forms of slavery in Cambodia’s brick manufacturing industry. It finds that despite the existence of comprehensive and long-standing legislation criminalizing the use of debt bondage and prohibiting child labour, competent authorities are making no efforts to eradicate them and are in fact enabling their survival.

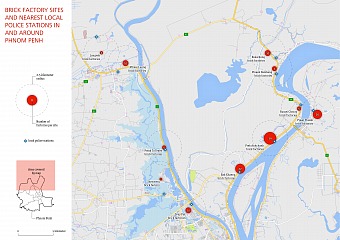

“Debt bondage and child labour are rife in Cambodia’s brick factories, many of which are in plain sight just a few miles from the capital city. Police stations and commune offices are located close by, often overlooking the factories, and the authorities know exactly what’s going on inside,” said Am Sam Ath, LICADHO’s Monitoring Manager. “It’s a scandal that this is going on and the government must intervene to bring it to an end immediately.”

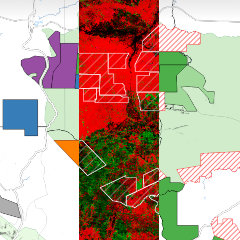

The report is based on a study of Cambodia’s main centre of brick production in an area to the north of Phnom Penh (see map), from where hundreds of trucks travel each day to supply the city’s booming construction sector. 11 sites were identified, containing over 100 factories and thousands of workers. The study involved interviews with around 50 workers, including adults and children.

The report details how factory owners recruit workers by issuing loans and providing housing to poor and desperate families. The factory owners secure the loans against a promise from the workers that they will work in the factory until the loan is repaid. However, pay in factories is so low that workers struggle to earn enough to subsist let alone pay back their debt and many end up taking more loans from the factory owners. The initial need for the families to borrow commonly arises as a result of a crisis such as sickness in the family or crop failure and the starting loans are small, often only a few hundred dollars. However, over time the debts grow and workers interviewed for the research were in debt for sums ranging from US$1,000 to US$6,000, amounts that they will never pay off. When debt reaches these levels, it can pass from one generation of a family to the next and the study found some families with three generations all working to pay off a debt that was originally taken on by a member of the oldest generation.

There are many children working in the brick factories and in the area studied most parents said that at least some of their children work. There is a considerable incentive for this because, rather than being paid a salary, workers are paid by the piece. This means that as more family members join the workforce, the number of bricks produced rises and the family income increases.

“Parents don’t want their children to work. They know it’s dangerous and they want them to go to school and have a better future”, said Naly Pilorge, LICADHO’s Deputy Director of Advocacy. “But with wages so low that they can barely feed the family, they don’t have a choice. As a result the children end up trapped by debt just like their parents.”

The report also covers the hazardous working conditions in brick factories and the appalling and unsanitary living conditions of the factory housing. It gives examples of severe injuries to brick factory workers, in particular children who have lost arms in brick factory machinery. It finds that as a consequence of their total dependence on the factory owners and their fear of reprisals, workers are unwilling to challenge their conditions or their treatment, and that despite persistent breaches of the criminal and civil law on the part of brick factory owners, the authorities responsible for enforcing the law take no steps to do so.

The practices of debt bondage and child labour are responsible for trapping multiple generations of families in a repeating cycle of poverty and servitude

The report concludes that together, the practices of debt bondage and child labour are responsible for trapping multiple generations of families in a repeating cycle of poverty and servitude. The beneficiaries of these practices are the factory owners who profit from a cheap and easily exploitable workforce and the buyers of bricks, from private individuals to large-scale developers, who are able to purchase bricks for a price that does not represent the true value of the labour that goes into making them.

The report calls on the Cambodian government to take immediate steps to free all bonded brick factory workers by ordering the immediate cancellation of all existing debt between brick factory owners and bonded workers. It calls on foreign governments to ensure that international investors are aware of the role played by debt bondage and child labour in the Cambodian construction industry and to support the Cambodian government to bring about their elimination.

For more information, please contact:

▪ Ms. Nap Somaly, Senior Women's and Children's Rights Monitor, mon4@licadho-cambodia.org, +855 (0)12 251 118 (Khmer)

▪ Ms. Naly Pilorge, LICADHO Deputy Director of Advocacy, advocacy@licadho-cambodia.org, +855 (0)12 803 650 (English)

PDF: Download full statement in English - Download full statement in Khmer

MP3: Listen to audio version in Khmer

- Related Material

- Topics

- Children's rights Courts, judiciary & rule of law Forced labour & debt bondage Labour rights